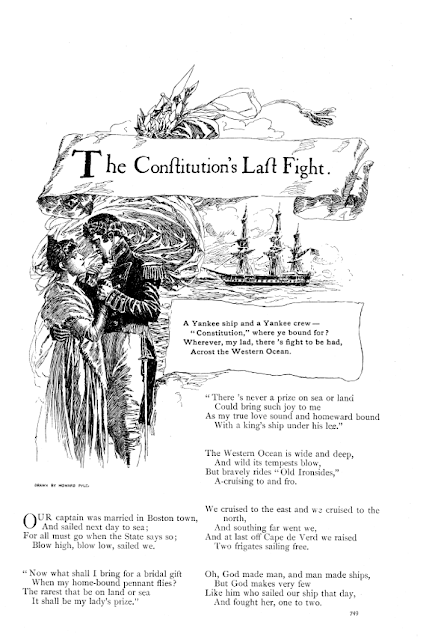

The Ballad and the Backstory: Fact and Fiction in "Constitution’s Last Fight" by James Jeffrey Roche

Who was this captain's wife? Did she really ask for a British ship for a bridal gift? Was the captain's bride quite satisfied with the one prize laid at her feet?

Far from it. This ballad is a romance, but hardly a historical one. What inspired James Jeffrey Roche to write it in 1895? And why, having composed one of the best and most factual descriptions of a naval battle ever put into poetry, did he whitewash the political machinations of a naval wife who destroyed her husband's career as the first commodore of the Pacific fleet?

Journalist, author and diplomat James Jeffrey Roche was born in Queens County, Ireland and raised on Prince Edward Island. He attended St. Dunstan's College and moved to Boston in 1866. Roche became assistant editor of The Pilot in 1883, and later published poetry and other literary works, including a biography of John Boyle O'Reilly. He served as editor of THE PILOT, and American Consul in Italy and Switzerland.

The Backstory

The battle described in the song took place off the African coast in February 1815, three days after peace had been declared in the War of 1812 (similarly to the Battle of New Orleans). On February 20, sixty leagues south of Madeira, Captain Charles Stewart captured HMS Cyane and HMS Levant. He took his prizes to Porto-Praya, capital of the Cape Verde Islands, arriving on March 7.The third ship in the song probably refers to a sequel of this battle. On March 11, three other British men-of-war arrived in Praya, and startled the three now-American ships out of harbor. All three British ships chased the Levant and HMS Acasta captured her, while the Constitution escaped with the Cyane: “the one prize laid at the feet” of the captain’s bride. The reference to “fighting one to two” likely refers to the first battle, “one to three” to the second.

This was the Constitution’s last military engagement, although her last official prize was a slave ship captured in 1853. Captain Stewart preserved the perfect battle record of his vessel, being never defeated or boarded since her first commission in 1800. Both the Constitution AND Captain Stewart were nicknamed “Old Ironsides,” and a gold medal was struck for the victory.

Captain Stewart (1776-1869) went on to become a Commodore and Rear Admiral, and his name was given to a US Naval destroyer, USS Stewart, launched in 1902 and sponsored by his granddaughter. Stewart was of Irish parents, and one of his daughters (Delia Tudor, named for her mother) became the mother of the Anglo-Irish nationalist Charles Stewart Parnell, later famous as “the uncrowned king of Ireland.”

“The captain's bride” was Delia Tudor (1787-1861), sister of Boston “ice king” Frederick Tudor. Her brother made his fortune (went to debtor’s prison, and earned it back) shipping ice from Boston ponds to the West Indies. The song takes liberties with the wedding date, which was on Thanksgiving Day, 1813 at Trinity Church. Constitution was in dry dock for most of 1813, blockaded in Boston by the English in 1814, and finally sailed on patrol in early 1815.

Could Delia really have asked for a British warship as a wedding present? Possible in character, unlikely in politics. The Tudor biography describes Delia and her sisters as “outspoken and determined” and “unusually spirited and attractive girls.” Her father was a Harvard lawyer who joined Washington’s army in Cambridge. However, their mother was of Tory stock, and the Tudor children grew up receiving, and being received by, both English and French royalty and nobility.

Delia was just returned from a two-year European tour of Napoleon’s court when the family went bankrupt, as the ice trade ran afoul of the blockade of Havana. Brother Frederick seems to have been a regular Boston burglar, “sporting” with the family funds until his “character was taken and he was sent to jail” in 1812 at the age of 28.

Delia’s marriage proved the solution to her fortune at least. In 1813, Captain Stewart was newly arrived in Boston to take up command of the Constitution after her victories over the Guerriere (under Isaac Hull) and the Java (under William Bainbridge). He was 35, “bluff and rough,” popularly supposed to resemble Nelson, and “believed to be rich” from his career in the Napoleonic Wars. Frederick Tudor’s biography calls it, however, a “cruelly ill-starred match,” which ended in permanent separation if not actual divorce.

Following Constitution’s last fight, Stewart was promoted to Commodore of the Franklin in the Mediterranean and by 1820 given command of the Pacific fleet. Delia joined her husband on the Franklin for the Pacific voyage, which resulted in “the only blot on [his] career.”

“Toward the end of his period of command in the Pacific, Mrs. Stewart supposedly smuggled the deposed President of Peru on board the Franklin without her husband’s knowledge. This act apparently caused an international crisis and Stewart himself, after relinquishing command of the Pacific squadron in 1823 or 1824, was up on charges before a courts-martial because of his involvement in the affair. Stewart was either reprimanded or censured as a result of this action. Stewart either divorced or separated from his wife almost immediately thereafter, and probably as a result of the previous affair.” (USS Stewart biography)

A woman whose father talked with King George for hours at a stretch, whose mother spoke French with the Empress Josephine, a woman who sailed around the Horn on a naval vessel to smuggle Simon Bolivar aboard the flagship of the Pacific fleet, then wrote President Monroe herself when her husband was court-martialed for her actions? Such a woman might well demand—and receive—a captured ship of the line for a bridal gift, along with her portrait by Gilbert Stuart. It seems the captain’s bride was as much of an Old Ironsides as her captain and his ship.

Comments